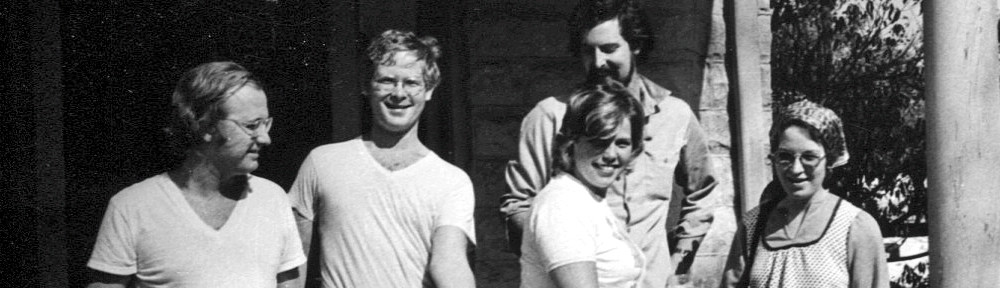

No one knew more interesting people or places than Charlie. For that matter, I’m not sure Charlie found anyone or any place ordinary. So when he suggested we take a drive to someplace called Voodoo Village… it sounded like a good way to kill a little time. Seems like it was a Saturday or Sunday afternoon…maybe 1971. Must have been a weekend because there were several of us hanging around the house on East Moreland Street.

We loaded into Joanne’s red Plymouth Duster. Charlie was driving since he knew how to find Voodoo Village and Barb and I were in the front seat. RP and JoAnn were in the back, maybe someone else.

Charlie snaps pix as we drive by Voodoo Village.Voodoo Village was nothing more than a few houses on a dead-end street in remote southwest Memphis. Before we pulled in, Charlie asked me to drive so he could take some pictures.

I drove past a couple of small houses with what appeared to be some really interesting lawn art. I don’t know how many photographs Charlie took as we drove past because I was eager to get turned around.

I turned the car around in a cul-de-sac a the end of the road and headed back the way we had come. Off to the left, from the houses we’d just past, a couple of young men appeared to be coming out to the street to meet us.

As I drew even with the houses, one man had come into the street and was gesturing for us to stop. Which would have been the normal thing to do with someone standing in the middle of the street. But somehow I never considered stopping. Not for a second. In fact, I put it to the floor. And never swerved. The fellow got out of the way and I must have been doing 50 by the time we pulled back onto the highway.

It’s impossible to tell from the photograph above so you’ll just have to take my word for it. The gentleman in the stripped shirt is holding what appeared to be a machete, down behind his right leg. He probably wanted to sell it to us as a souvenir. Or maybe he wanted to hack on a bunch of nosey white kids with no respect for other people’s religion or privacy. And who could blame him.

UPDATE: Podcast on history of Voodoo Village (July 3, 2017)

News Stories about Voodoo Village

“We have an eternal organization here. A church. Our temple is the most beautiful place in the world. All these things have a meaning. They are symbols of God.”

A canvas awning was pulled back, and he motioned into the temple. The floor, walls, and ceiling were covered with colorful pieces of satin. The little building was filled with other symbols and dolls, illuminated by tiny electric lights.

“It took me four years to make this. Sometimes I would go in in the morning and not come out until the next. How did I do it? By the power of God.”

— By Charles A. Brown, Memphis Press-Scimitar, July 31, 1961

Located at 4596 Mary Angela Road – a dead-end stretch of asphalt in a remote southwest corner of the county – it first attracted public attention in the early 1960s when a series of confrontations broke out between carloads of sightseers and youths dwelling inside the fenced-in compound.

At the time, Harris scoffed at the idea that his puzzling creations had anything to do with the black arts. On the contrary, he called his retreat “St. Paul’s Spiritual Temple” and said it was holy ground.

“Don’t come too close, don’t stop too long and don’t take no pictures,” a reporter was told as he parked his car outside the village. Inside the fence are several houses; a homemade temple decorated with crosses, hearts and sunbursts; a half-dozen cars; and countless pieces of handicraft that look like something that might be found in the Twilight Zone between Alice’s Wonderland and the Wizard’s of Oz.

At first glance, much of it looks like the exaggerated objects in a children’s playground –a candle 8 feet tall, a set of wheels connected by a crosscut saw, a giant figure with outstretched arms, fans, spindles, spinners, all in rainbow colors—but the mood is serious rather whimsical.

“All this that you see is my craft,” he said. “It is the work of one man, and don’t nobody know what it means but me. People are always coming here trying to me to talk about it, but I don’t discuss it with anyone. If I give it away (the secret, he means) what have I got?”

There’s one gizmo with a propeller big enough to take off and another that looks like a Thunderbird with a pair of horns. There are painted stumps and towering crosses. There are things that make your head real to look at them.

“I’m the only one who understands it,” he said. “God told the black man and the Indian some thing he didn’t tell nobody else. The only way you’re ever going to find out what all this means is to get like me.”

— William Thomas, Commercial-Appeal, July 14, 1984

“Voodoo Village has been a wellspring of speculation and myth for several decades, and has even been incorporated into the name of a popular local band, the Voodoo Village People.

Voodoo Village technically operates under the name of St. Paul’s Spiritual Temple. To get there, you have to literally drive to the end of the Memphis city map to Mary Angela road in remote Southwest Memphis. The compound contains several shotgun shacks surrounded by a dizzying array of gigantic, freaky-to-the-unknowing monuments. Tall crosses line up like soldiers, carved crescent moons and stars perch on poles, horns stick out of tree trunks, and larger-than-life Egyptian-type masks stare down at unwelcome visitors. While some of the objects are eerie and some just plan amusing, all are painted in a rainbow-bright spectrum of colors. Overall, the effect is both startling and striking, resembling a sprawling playground constructed by a near-sighted artist on hallucinogens.

The artist in this case, however, is Wash Harris, a reclusive man who has claimed in the past to be part African-American and part Indian. Reportedly in his early 80s now, Harris has grown tired of the curiosity his commune inspires and has ceased speaking with those who are merely intrigued. I had been told that its’ nearly impossible to talk with him, and that, in fact, gaining entrance to Voodoo Village would be highly improbable.

As we cruised by the first time, entering seemed unlikely. The entire site is surrounded by a metal fence and the main driveway is blocked by a heavy iron gate. When we returned just minutes later, however, the gate was flung wide open. I parked the car, facing the main road (having been warned not go get trapped in the dead-end street), and we quietly slipped inside the compound, wondering how many eyes might be watching. We marveled at the rough craftsmanship and artistic intricacy of the displays, which looked like products of a whittling disciple of Salvador Dali.

Hearing voices in the shack behind me, I apprehensively mounted the steps. After several knocks, a woman in a white tunic and head-wrapping cracked the door.

“You didn’t take any pictures, did you?” she asked. I had the impression that several people were moving around behind her in the darkened room.

I asked if I could talk to whoever was in charge, but she said I should go away, that maybe I could talk to someone later. I suspected this was just get the gate closed behind us again. As we walked toward the gate, a wrecker backed down the gravel driveway and blocked our path. A man wearing a gas station uniform hopped out, smoking a stubby cigar.

“Did you take any pictures?” he demanded.

I told him we were simply interested in the purpose of the commune and in the art work.

“Are you in a lodge?” he asked, referring to what I assumed had to be the Masonic organization (Wash Harris was reportedly a member of the Masonic Lodge for many years). When I told him I wasn’t, he replied, “Then you can’t understand.”

The man identified himself as James Harris, 40, son of Wash Harris. “What’s the name you heard for this place?” he blurted at me. When I said “Voodoo Village,” he blurted back, “That’s the name the peckerwoods gave it.”

Regarding any supernatural aspect of the ominous structures looming over the compound, James Harris said, “Everything here represents something from the Masons or the Scripture.”

— Steven Russell, The Memphis Flyer, October 26, 1989

A sheriff’s deputy arrested three youths early yesterday after a cursing and shooting incident near “Voodoo Village” in southwest Shelby County. The deputy was on still-watch on Mary Angela Road when the youths drove up and started cursing. A gun was fired and the youths attempted to flee before the deputy stopped them and placed them under arrest. The name “Voodoo Village” has been given to the area because of figures and symbols in the yard of Wash Harris of Mary Angela. He calls his home St. Paul’s Spiritual Temple.

— Commercial Appeal, May 15, 1990

Pingback: The Truth Behind Voodoo Village - Memphis Type History